In an era defined by oversharing and offering our private lives to the public, a counter-trend of privatization is reshaping commercial real estate. Restaurants, gyms, and other traditional “third spaces” are increasingly catering to smaller, more selective cohorts. From the Aman Resort luxury spa network to Soho House’s global work/play hubs, commercial spaces are transforming into members-only environments. By some estimates, the global private members’ club market is expected to break $25 billion by 2027, with the Soho House alone valued at $2.7 billion, according to those looking to take the company private.

Privatization in real estate is fueled by a number of trends, of course. To name a few: the insatiable demand for luxury amenities and gated environments (aka “flight to quality“), a steady pullback in public investment in community spaces and services (especially at the federal level), and the triumph of remote work over the office space (the unheralded “second space” in our lives).

Yet, while the headlines about private clubs focus on high society and luxury veneer, the history of private clubs is far richer, and the legal framework for the creation of private societies offers the general public much more than is commonly understood.

This article explores some of the civic achievements that private social clubs can take credit for, unpacks some of the legal structures and benefits of forming your own society (or club, charity, trust, “friends of” group, etc.), and provides some insights into the unique challenges and opportunities such groups present in the commercial real estate space.

More than Country Clubs: the Civic Side of Private Clubs.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, a tale that immortalized the excesses of the Roaring Twenties’ private clubs and exclusive gatherings. But, while the Gatsby clubs may have been fueled by greed and an inferiority complex, less glamorous yet mission-driven clubs have been fostering social progress and culture for far longer.

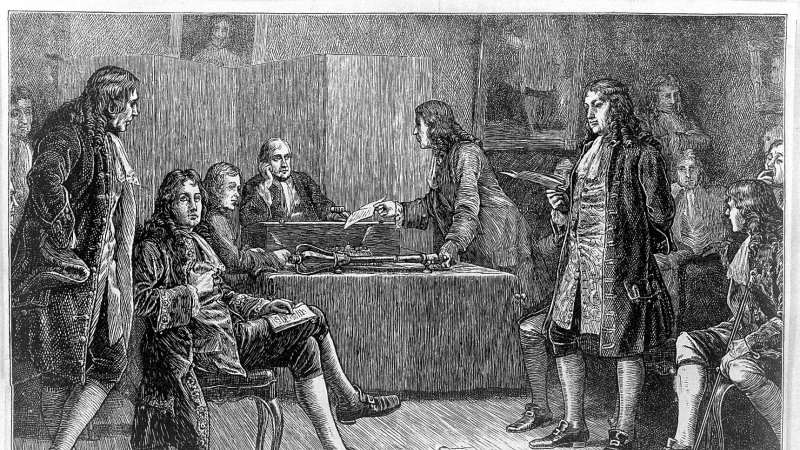

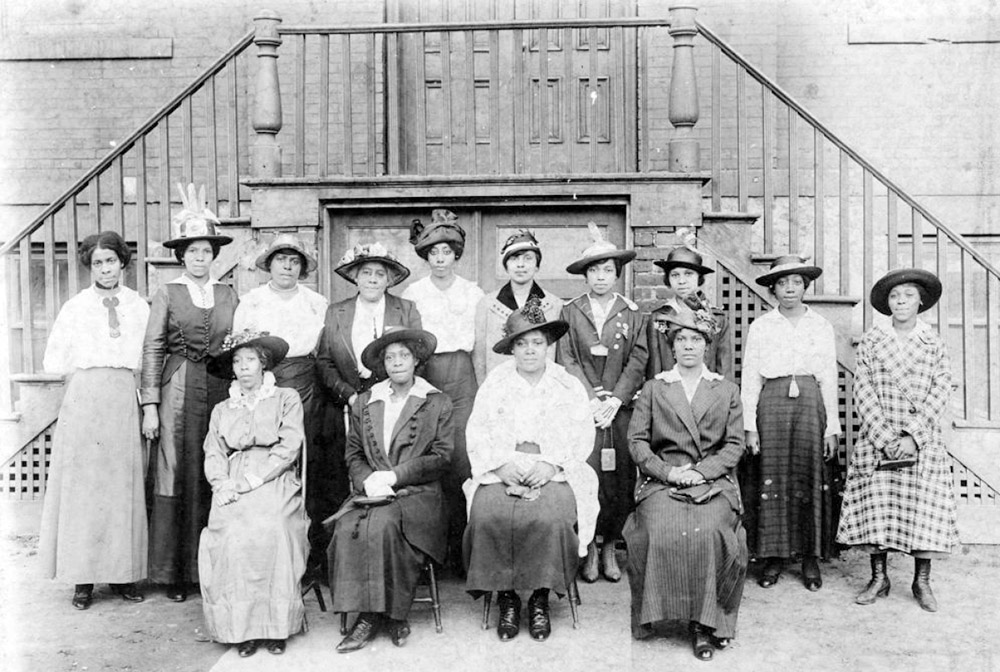

Take London’s Royal Society for Improving Natural Knowledge, for example. Founded in 1660, this private organization (pictured above) sponsored the pioneering works of Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle, helping to shape modern science. Social revolutions, from abolition and women’s suffrage, have been stoked by private groups like the Phyllis Wheatley Club (pictured above). Artistic collectives, from the historic Bloomsbury Group to Warhol’s Factory to today’s NeueHouse and Solas Studio, continue to mold the arts world. Not to mention the proliferation of modern sports and pastimes fostered by sporting clubs and associations, beginning with soccer’s oldest club, the Sheffield Football Club (“assoc.” being the derivation of “soccer” after all). Add to that, countless relief organizations and charities, such as the Red Cross and the International Rescue Committee (fun fact: both founded by former patent clerks, Clara Barton and Albert Einstein).

Lest I veer further off track, I’ll refrain from listing the famous cocktails (Manhattan, Manhattan Club, 1870’s), snacks (Oysters Rockefeller, Antoine’s, 1899) and dishes (the Club Sandwich, Saratoga Club-House, 1894) that have jumped off club menus of the past.

Tapping the Adirondack public-private partnership, courtesy of the Ausable Club and other private societies, duty-free

The U.S. conservation movement may be synonymous with the Sierra Club (co-founded by John Muir in 1892), but it owes just as much to the lesser-known Ausable Club of Keene Valley, NY. In 1886, as clear-cut logging began to despoil the Ausable Lakes, private citizens formed the Adirondack Mountain Reserve to purchase and protect 25,000 acres of wilderness. This group’s wilderness refuge (later renamed the Ausable Club) created the template for the eventual 6.1 million-acre Adirondack Park. The Adirondacks is not only the largest protected area in the U.S., but arguably the nation’s largest and most successful public-private partnership. While the state-owned 2.7 million acre “Adirondacks Forest Preserve” region (along with portions of the Catskills) is famously by the “Forever Wild” clause of the NY State Constitution (Article XIV), it’s the private stewardship of the remaining 3.5 million acres that makes the Adirondacks what it is. A majestic public-private partnership covering over 20% of New York, all thanks to a social club’s actions more than 100 years ago.

Club Rules through History

“… to further promoting by the authority of experiments the science of natural things and of useful arts, to the glory of God the Creator, and the advantage of the human race.” – initial charter for the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge

“Weaving spiders, come not here.” – a founding credo of San Fransisco’s Bohemian Club, 1870’s. Lifted from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and a precursor to the modern “turn your $*@_ phones off” club policy.

“Pushing with the Hands is allowed but no Hacking (or tripping up) is fair under any circumstances whatsoever.” – an original and influential sporting rule of the Sheffield Football Club, 1860’s

Letter of Recommendation: Anyone interested in learning more about social clubs, their buildings, and their by-laws should consider subscribing to the sumptuous Clubland Substack by Dr. Seth Thévoz. Quite on topic – its recent post is devoted to the legal manuals and checklists for making clubs run smoothly.

Legal Toolkit for Clubs and Place-Based Organizations:

For those looking to organize, whether to preserve a community garden, create a new arts space, or manage a shared building, a powerful set of legal tools exists. These structures enable private organizations that control real estate to operate effectively, secure funding, and achieve their mission. Here’s a brief breakdown of some key legal tools available, as well as some key considerations for those managing private social clubs or organizations within commercial real estate.

Choosing the Right Entity Structure:

- The Charitable Organization: 501-c-3. This is the most common structure for non-profits dedicated to charitable, religious, educational, scientific, or literary purposes. Governed by the Internal Revenue Code at $26 U.S.C. § 501-c-3, its key advantage is that donations are tax-deductible for the donor, making fundraising much easier. These organizations are eligible for a wide range of public and private grants.

- The Social Club: 501-c-7. This structure, governed by $26 U.S.C. § 501-c-7, is for non-profits organized for “pleasure, recreation, and other nonprofitable purposes.” Think tennis clubs, alumni associations, or hobby groups. Crucially, dues and donations are generally not tax-deductible. Their income from membership activities is tax-exempt, but income derived from non-members (e.g., renting out their space for a wedding) can be subject to Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT).

- The For-Profit Membership Model. Private social clubs like the Soho House are typically structured as for-profit Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) or Corporations, as opposed to Non-Profits. Their goal is to generate profit for their owners by selling exclusive access and services. While they don’t have tax exemptions, they have far more flexibility in their operations and use of funds. In certain jurisdictions, private corporations that seek to mix a profit motive with civic objectives can form as a Benefit Corporation. (e.g. filing under New York’s BCL 1702), or can apply (and pay) for 3rd party certifications such as B-Corp.

Tax Exemptions for Certain NFP Interests:

- New York: Charitable organizations that own property may be eligible for a full or partial exemption from local property taxes under New York Real Property Tax Law (RPTL) § 420-a. The standard is strict: the property must be used “exclusively” for the organization’s stated charitable purpose. This “exclusive use” test is frequently litigated (see, e.g., Matter of Symphony Space, Inc. v. Tishelman, 60 N.Y.2d 33 (1983)), and any portion of the property used for non-exempt purposes (like a commercial coffee shop) could be deemed taxable.

- Washington, D.C.: The District offers similar exemptions under D.C. Code § 47-1002. This statute exempts buildings belonging to and operated by institutions of learning, art, or charity, provided the property is not used for private gain. Like in New York, the D.C. Office of Tax and Revenue applies strict scrutiny to ensure the property usage aligns directly with the exempt purpose.

Opportunities and Minefields for Clubs in Commercial Lease Agreements:

- Use Clauses: The Right to Be Private: Your lease’s use clause must explicitly state that the space is for a private, members-only club to avoid conflict with a landlord who may want public access.

- Access Agreements: Protecting Your Privacy: Negotiate your lease to require the landlord to give prior written notice for non-emergency access, protecting your club’s privacy and operations.

- Sublease Concerns: Gaining Flexibility: To maintain the option to sublease a portion of your space, ensure the lease states that the landlord’s consent “shall not be unreasonably withheld.”

- Upper vs. Ground Floor: Location and Visibility: Depending on your floor, negotiate specific rights for either obscuring your ground-floor space for privacy or securing prominent signage for your upper-floor location.

- Zoning / Use Groups: The Right Use for the Right Space: Always confirm that a building’s zoning permits your club’s specific activities (e.g., live music, food service) to avoid legal issues and fines.

- Reporting Requirements: Confidentiality is Key: Limit the amount of sensitive information you must share with the landlord by negotiating for a confidentiality clause that protects your club’s proprietary data.

- Reputational Issues: Maintaining Your Brand: Protect your club’s reputation by ensuring the lease requires the landlord to maintain a high standard for the building and all other tenants.

Grant Programs for Non-Profit Organizations:

- While federal funding may be contracting overall, significant grant opportunities remain.

- Federal: Grants.gov is the centralized portal for federal grant opportunities. Agencies like the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) are key sources for cultural and educational clubs.

- New York: The New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) is a major funder for arts organizations. For groups focused on open space and parks, Parks & Trails New York (PTNY) offers dedicated grant programs.

- Washington, D.C.: The D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities (CAH) provides a wide array of grants to support D.C.-based nonprofits.

Best Practices for Governance & Operations:

- Bylaws as Constitution: Every club needs a clear set of bylaws. This is the internal operating manual that dictates how the organization is run. Key provisions should include: the club’s mission, membership requirements (classes, dues, rights, and expulsion procedures), the structure and duties of the Board of Directors, meeting and voting procedures (including quorum), and the process for amending the bylaws themselves.

- Zoning and Land Use: This is paramount. Most residential zones prohibit commercial activity. You may need to seek a variance or special permit from your local planning board — a costly and uncertain process.

- Liability / Indemnity: Robust insurance is non-negotiable. This includes general liability insurance, liquor liability if alcohol is served, and Directors & Officers (D&O) insurance to protect board members from personal liability.

- Anti-Discrimination Policies: While there are narrow exceptions for “distinctly private” clubs, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and numerous state and local human rights laws prohibit any discrimination based on race, color, religion, or other protected classes. The legal test for what constitutes a “distinctly private” club is complex and fact-specific (see Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609 (1984)), and operating in a gray area is a major risk, with various ethical and moral implications.

Personal Journey through ‘Clubland’

I’ll take a brief moment to reflect on some clubs and societies I’ve had the pleasure of cavorting with. Just this year I joined a club that exists at the polar opposite side of glamour from the clubs of Gatsby: the board of my 90-unit, 93-year old coop building. We are a small 5-person governing committee of shareholder neighbors who have volunteered (or been “volun-told”) to help manage our Building’s aging bones with a tight budget. Meetings are private, but I’m free to complain about it in general terms. For recreation, I’m lucky to call myself a member of the Knickerbocker Tennis Club, a scrappy assemblage of five har-tru courts and a humble clubhouse with a 130-year history and nearly as long a waiting list. Of all the private groups I’ve worked with, I am most proud to have served on the boards of New Yorkers for Parks and the Brooklyn Queens Land Trust, two great private organizations that work tirelessly to protect and grow NYC’s public spaces. Last, but not least, there’s the bylaw-less book club my friends and I formed in 2012, and still haven’t figured out how to dissolve.

Guilded Age: Form a Club That Would Have You as a Member*

*apologies to Groucho Marx. Images from Rushmore, 1997, courtesy of Touchstone Pictures

One of my modern fictional heroes, Max Fischer from the film Rushmore, perfectly embodies the positive role of private clubs. Despite limited means, Max created numerous clubs to pursue his passions, showing that a club’s power lies not in exclusivity but in offering structure, purpose, and a shared space for a common goal, even outside traditional measures of success. While private clubs can exclude, they are also a powerful tool for creation, a legal framework for organizing people around a shared mission without the drag of public procurement or government regulation. As public funding for community assets declines, private organizing offers a potent response, empowering people to define their mission, create their space, and build the world they want together.

Look around.

You may already be in a club, from a condo board to a parents’ association. The question is, what will you build with it?

—-